Kuba Empire: History, Culture, and Royal Heritage of Precolonial Congo

Kuba Empire: History, Culture, and Royal Heritage of Precolonial Congo

Discover the fascinating history, intricate culture, and royal heritage of the Kuba Empire, a powerful precolonial kingdom in Central Africa known for its artistry, governance, and legacy.

When people think of the grandeur of precolonial African kingdoms, names like Mali, Benin, or Songhai often come to mind. However, tucked deep within the heart of Central Africa, what is today the Democratic Republic of Congo once flourished a kingdom of remarkable sophistication, political structure, and artistic innovation: the Kuba Kingdom.

Founded centuries before colonial conquest, the Kuba Kingdom was not merely a kingdom by name; it was a complex federation of interrelated chiefdoms held together by governance, spiritual beliefs, economic exchange, and a culture of beauty and symbolism.

Origins of the Kuba Kingdom

The Kuba people trace their roots to the northern savannas near the Sankuru and Kasai rivers, a fertile area in today’s south-central DRC. According to oral tradition, the Kuba Kingdom was formed sometime in the early 17th century, around 1625, when a leader named Shyaam a-Mbul a-Ngwoom arrived from the north and united various Bantu-speaking groups under a centralized monarchy.

Before Shyaam’s unification, the region was home to several ethnic groups, such as the Bushoong, Ngeende, Kete, Coofa, and Leele, each with distinct leaders and customs. However, inter-communal rivalry and fragmentation weakened the region. Shyaam, regarded as a visionary leader, introduced new forms of governance and religious unification, ultimately founding the Kuba Kingdom.

Shyaam a-Mbul was not a mere conqueror. Oral legends say he traveled to neighboring societies, including the Loango and Kongo kingdoms, and studied their political and administrative structures. Upon returning, he implemented reforms that revolutionized Kuba society.

Political Structure: A Federation of Strength

The Kuba Kingdom developed one of the most intricate political systems in all of precolonial Africa. Unlike many centralized monarchies ruled strictly from the top, Kuba leadership was decentralized yet unified.

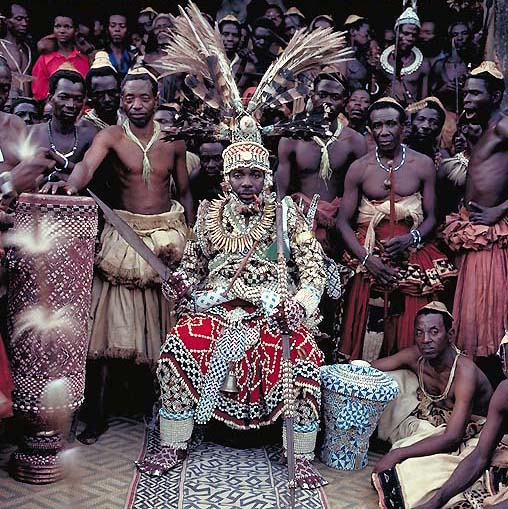

At the apex stood the Nyim, the king of the Bushoong (the dominant Kuba clan), who was seen as both a political and spiritual leader. His power, though vast, was checked by councils of nobles, priests, and clan representatives. This system allowed for internal balance and stability across different ethnic groups within the kingdom.

The kingdom was further subdivided into chiefdoms, each led by local rulers (called Mfumu or Ngwoom), who swore allegiance to the Nyim. These local leaders were given autonomy in internal matters but were expected to uphold Kuba unity and pay tribute to the capital.

One of the reasons for the kingdom's endurance over centuries was this federated model. It blended central authority with local governance, preventing rebellion and promoting cohesion.

Economic Prosperity and Trade

Kuba society thrived on agriculture, craftsmanship, and internal trade. The fertile river valleys allowed the Kuba people to grow crops like millet, yams, and palm oil, which sustained the population and supported trade.

Skilled artisans produced raffia cloth, carvings, drums, beaded jewelry, and intricately designed ceremonial masks. Raffia cloth, in particular, became a form of currency and a medium of social expression. It was used in trade, royal regalia, and religious rituals.

Markets within the kingdom were vibrant, and the Kuba traded not only among themselves but also with neighboring groups. The kingdom became a hub of artisanal exchange, where outsiders would come to obtain Kuba textiles, tools, and art.

Art and Symbolism: A Culture of Beauty and Identity

One of the most distinctive features of the Kuba Kingdom was its visual culture. Art was not just decorative; it was deeply spiritual, symbolic, and political.

Royal portraits, carved statues, and elaborate masks were crafted to immortalize rulers, deities, and ancestors. The Ndop statues, in particular, were carved from hardwood to represent the likeness of deceased kings. These were not mere effigies; they symbolized the king’s spirit and his achievements and were used in royal rituals.

Kuba masks were equally important. Used in initiation rites, funerals, and harvest festivals, they embodied ancestral spirits and cosmological forces. Each mask had a specific meaning and was worn only by designated individuals trained in sacred traditions.

The Kuba are also celebrated for their textile artistry. Kuba cloth, made from woven raffia, is still admired today for its geometric patterns, earthy tones, and cultural depth. These patterns often carried coded messages about social status, family lineage, and spiritual beliefs.

Religion and Cosmology

The Kuba cosmology was rooted in belief in a supreme creator god, known as Nyaim, and a pantheon of spirits that governed the natural world, ancestors, and social order.

The king (Nyim) was considered semi-divine, a representative of the gods on earth. Royal rituals included sacrifices, prayers, and festivals, particularly during planting and harvest seasons.

The Kuba also practiced ancestor veneration. Shrines were built in homes and palaces to honor forebears. Elders acted as custodians of spiritual wisdom and often served as diviners or spiritual guides.

Their calendar was marked by festivals such as the Royal Funeral Rite, a grand event involving music, dance, and elaborate masquerades that could last weeks and symbolized the transition of kings from the physical world to the ancestral realm.

The Role of Women in Kuba Society

Though kingship was patriarchal, women in Kuba society held significant roles in social, economic, and religious life. Elite women, especially those from royal families, served as advisors, spiritual leaders, and custodians of palace secrets.

Women also played a central role in raffia cloth production and local markets. Marriage among the Kuba was more than a romantic union; it was a social alliance between families and often involved extended negotiation, bridewealth, and ceremonies.

Education and Initiation

Education was not institutional in the modern sense, but the Kuba placed immense value on age-grade systems and initiation schools. Boys and girls underwent initiation rites that introduced them to adult responsibilities, history, spiritual beliefs, and social etiquette.

The Bush Schools were secretive training camps where young males were taught warfare, farming, leadership, and sacred songs and stories.

This form of education preserved cultural continuity and ensured that the Kuba heritage was transmitted from generation to generation.

Foreign Contact and Colonization

The Kuba Kingdom remained largely insulated from external threats due to its geographical position. However, with the European Scramble for Africa in the 19th century, especially under Belgian colonization led by King Leopold II, the Kuba people were eventually drawn into colonial rule.

When European explorers first arrived, they were awed by the Kuba’s sophistication. German explorer Hermann Wissmann and later American explorer William Sheppard documented their visits with admiration for Kuba's political systems, art, and architecture.

But colonization brought disruption. The Belgians, seeking to control the Congo for rubber and other resources, undermined local leadership, imposed taxation, and introduced forced labor. Though the Kuba resisted, the Belgian state gradually eroded their autonomy.

Legacy and Contemporary Significance

Despite the upheavals of colonization, the Kuba identity has endured. Today, descendants of the Kuba people still live in central DRC, preserving their language, art, and oral traditions.

Their contributions to African history and global art are increasingly recognized. Kuba textiles, masks, and sculptures are housed in major museums across the world, from the Louvre in Paris to the Smithsonian in Washington.

Efforts are also underway to revive traditional governance systems, document oral history, and teach young people the cultural legacy of their ancestors.

The Kuba story is a powerful reminder of the richness of African civilization, the strength of indigenous systems, and the creativity that thrived long before and beyond colonial imposition.

Conclusion

The history of the Kuba Kingdom is not a tale of obscurity. It is a brilliant chapter in Africa’s past, filled with political genius, artistic mastery, and cultural integrity. From Shyaam a-Mbul's founding vision to the contemporary revival of Kuba heritage, this Central African kingdom stands as a testament to the diverse and dynamic history of the continent.

In a world that often centers only a handful of African empires in mainstream narratives, the Kuba Kingdom deserves its rightful place among the great civilizations of the world. Its story, told through carved wood, woven cloth, and living memory, continues to inspire those who seek to rediscover the real face of Africa, one kingdom, one people, one heritage at a time.