The Efik People of Nigeria: History, Culture, and Legacies

The Efik People of Nigeria: History, Culture, and Legacies

Meta Description: Explore the rich history, vibrant culture, and lasting legacy of the Efik people of Nigeria, known for their traditions, trade, and influence in West African society.

The Efik are one of Nigeria’s most culturally rich and historically significant ethnic groups. With their roots firmly planted in south-south Nigeria, primarily in Cross River State, the Efik have carved a unique space in West African history as traders, administrators, scholars, and cultural bearers. From their early migrations and political structures to their religious beliefs, festivals, and influence in international trade, the Efik people have left a lasting mark on Nigeria’s identity.

In this blog, we’ll take a deep dive into the origin, development, culture, and influence of the Efik people, providing you with an in-depth understanding of who they are and why they matter.

Origin and Early Migrations

The Efik people trace their origins to the Iboku clan, believed to have descended from the larger Bantu-speaking groups that migrated from Central Africa thousands of years ago. Over time, this group began settling in what is now south-south Nigeria and parts of Cameroon, forming what anthropologists consider the earliest ancestors of the Efik, Ibibio, and Oron ethnic groups.

From ancient oral traditions and linguistic studies, the Efik people are often linked to the broader Ibibio-Efik family, though they eventually developed a distinct dialect, customs, and political identity that set them apart.

Migration from Uruan: A Journey for Trade, Identity, and Space

The most widely accepted narrative places their departure from Uruan, a town in present-day Akwa Ibom State. The Efik left Uruan primarily due to internal conflicts, population pressures, and the quest for economic opportunities. Some accounts also suggest leadership disputes and spiritual revelations as factors influencing their migration.

This migration was not a single movement but occurred in waves over centuries, with each group establishing temporary settlements and then moving further until they reached the banks of the Cross River. These journeys were arduous, involving dense forests, rivers, and confrontations with other communities.

Settlement Along the Cross River

Upon reaching the lower Cross River basin, a region with rich mangroves, riverine access, and fertile land, the Efik found ideal conditions for settlement and trade. They began founding communities like:

- Obutong (Creek Town)

- Atakpa (Duke Town)

- Ikot Ansa and Henshaw Town

These areas soon evolved into vibrant city-states under various Efik ruling houses. By strategically situating themselves along navigable waterways, they were well-positioned to connect inland communities with European traders who arrived via the Atlantic Ocean.

Cultural Separation and Identity Formation

Although closely related to the Ibibio, the Efik began asserting a unique identity influenced by their new environment, interactions with European traders, and growing economic power. Their language, Efik, started to diverge, and their customs, naming patterns, religious practices, and dress began to reflect a more coastal and trade-centered culture.

They adopted fishing, boat-making, and navigation as core skills and developed elaborate customs that emphasized trade diplomacy, spiritual rites, and kinship. By the 17th century, they had evolved into a highly organized society with a strong maritime economy and distinctive sociopolitical institutions.

Why Migrate Further?

Even after initial settlements along the Cross River, internal disagreements, trade competition, and territorial ambitions led to further dispersion. Some Efik families moved to other parts of the Cross River region, such as Ikot Offiong, Ikot Omin, and even parts of modern-day Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea.

Wherever they settled, the Efik maintained strong cultural cohesion through shared dialect, religious institutions like the Ekpe society, and common historical narratives that traced their lineage back to Uruan and ultimately to ancient Bantu roots.

Political Structure and Leadership

Efik society evolved with a centralized but consultative political system, often led by powerful Efik kings (Obongs) and councils of elders. The most powerful ruling house was in Duke Town (Atakpa), where the Obong of Calabar emerged as a key traditional ruler.

Power was balanced among several noble families, and important matters were decided through deliberation and community consensus. Over time, the Ekpe society became a central part of the Efik political and spiritual structure. It was responsible for law enforcement, social organization, and initiation rites, functioning as both a judicial and spiritual authority.

The Ekpe Society and Nsibidi Writing

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of Efik cultural heritage is their Ekpe society, a powerful, secretive group that combined spiritual authority, social organization, and law enforcement.

The Ekpe society was responsible for governing behavior, punishing wrongdoers, initiating new members into adulthood, and maintaining social harmony. Membership was open to men of standing and was a source of great prestige.

Through the Ekpe society, the Efik also developed a visual symbolic system called Nsibidi, a precolonial writing system composed of pictograms, ideograms, and codes. Nsibidi was used to write messages, record laws, and pass down cultural values. Today, Nsibidi is studied by linguists and historians as one of Africa's few indigenous writing systems with a long recorded past.

Role in Precolonial Trade

Due to their location and seafaring skills, the Efik became prominent players in Atlantic commerce. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, they acted as intermediaries between European merchants and African traders from the hinterlands.

This trade included palm oil, ivory, and regrettably, enslaved people. The Efik were key facilitators of the transatlantic slave trade from the Bight of Biafra, particularly in Old Calabar, which was one of the most active slave export hubs in West Africa.

This interaction brought immense wealth and influence to Efik merchants. Their elites grew literate in English, adopted European names and customs, and participated in diplomacy with British officials. The long-standing relationships between the Efik and the Europeans also resulted in the early adoption of Christianity and Western education in Efik land.

The Arrival of Christianity and Western Influence

The Efik were among the first Nigerian groups to accept Christianity, owing to their early contact with missionaries such as Rev. Hope Waddell of the Church of Scotland Mission in the mid-1800s. The missionaries established schools, churches, and printing presses in Calabar, helping to spread literacy and Christian values.

The Efik Bible translation was among the earliest African Bible versions. This helped preserve and develop the written form of the Efik language. The missionaries also supported the abolition of the slave trade, often working with Efik leaders to dismantle old trade networks and replace them with palm oil commerce.

This fusion of traditional culture and Christian influence continues to shape Efik society today.

Language, Names, and Cultural Identity

The Efik language belongs to the Benue-Congo branch of the Niger-Congo family. It shares similarities with Ibibio and other Cross River languages but retains unique expressions, tones, and cultural idioms.

Due to close interaction with Europeans, many Efik names and surnames were either directly translated or adapted into Anglicized forms. This is why many Efik people bear names like Henshaw, Duke, Ephraim, Archibong, and Cobham. These names often reflected diplomatic and business ties with Europeans or were adopted during Christian baptism.

The use of English names doesn’t diminish their African identity; instead, it reflects a hybrid culture shaped by trade, diplomacy, and resilience.

Religion and Spiritual Practices

Although Christianity has become widespread among the Efik, traditional religion still plays a role. The Efik cosmology included a belief in a supreme creator (Abasi Ibom) and several intermediary deities. Rituals involved sacrifices, festivals, ancestral worship, and divination.

Spiritual ceremonies were performed to bless marriages, initiate leaders, and purify the land during crises. Even today, elements of traditional religion are seen during important Efik cultural festivals and rites of passage.

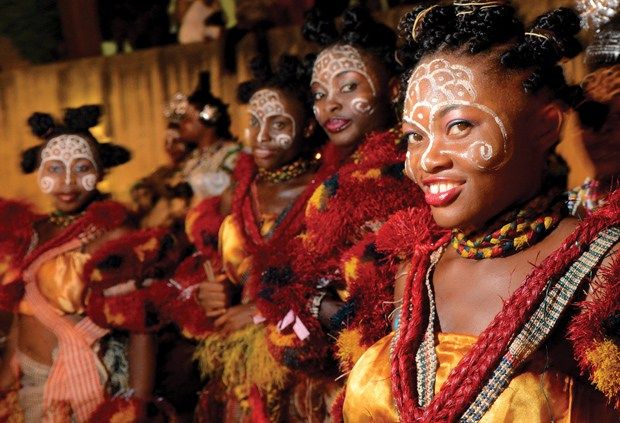

Festivals and Cultural Expressions

The Efik calendar is filled with vibrant festivals that display the people’s rich clothing, dances, and masquerade performances.

Notable among them is the Ndok Festival, where symbolic effigies (Nabikim) are paraded and then destroyed to drive away evil spirits and misfortunes.

The Ekpe Masquerade is another iconic celebration. Dancers wear elaborate masks and regalia, performing sacred rites as part of the secretive Ekpe society. These festivals are not just entertainment; they reaffirm social order, celebrate ancestors, and preserve cultural memory.

Marriage Customs and Social Life

Marriage among the Efik is an elaborate process that involves family negotiations, symbolic exchanges, and lavish ceremonies. Traditional Efik marriages begin with a knocking ceremony (Mbop Iso), where the groom’s family formally seeks the bride’s hand.

This is followed by a list of requirements, such as drinks, foodstuffs, wrappers, and gifts for elders. The bride’s character and upbringing are praised in poetic expressions called "Mbopo", and she often undergoes a fattening process. In this symbolic rite, she is pampered and prepared for womanhood and marital life.

Efik weddings are colorful, detailed, and deeply cultural, preserving values like respect, unity, and family honor.

Dress and Culinary Culture

Efik attire is among the most elegant in Nigeria. Men wear long embroidered shirts (Etibo), trousers, and caps, while women dazzle in wrappers (Iba), beaded necklaces, and shimmering blouses. On special occasions, they adorn themselves with coral beads and traditional fans.

In terms of food, the Efik are culinary experts. Their dishes include:

- Edikang Ikong (vegetable soup)

- Afang Soup

- Atama Soup

- Ekpang Nkukwo (grated cocoyam and fish cooked in leaves)

These meals are prepared with precision, often served during festivals and ceremonies to reflect wealth, hospitality, and status.

Modern-Day Efik and National Relevance

Today, the Efik continue to be relevant in Nigeria’s sociopolitical scene. Calabar remains an important economic and cultural hub, hosting Nigeria’s famous Calabar Carnival every December.

The Efik have produced scholars, statesmen, writers, and activists who contributed to national development. From Mariam Eyo Ita to Prof. Okon Uya, their legacy is expansive and proud.

The Preservation of Efik Heritage Project and other diaspora-led initiatives aim to revive and document lost traditions, encourage younger generations to learn the Efik language, and retain cultural identity in an increasingly globalized world.

The Efik people are not just a footnote in Nigerian history. They are central to the country's cultural, political, and historical journey. Their contribution to writing systems, trade, diplomacy, religion, and modern governance proves that African societies were never “primitive” or “uncivilized” before colonialism; they were dynamic, adaptive, and sophisticated in their own right.

Understanding the Efik story helps paint a fuller picture of Nigeria’s mosaic identity. And if we want future generations to grow up proud of who they are, we must amplify stories like these, not just the familiar ones.